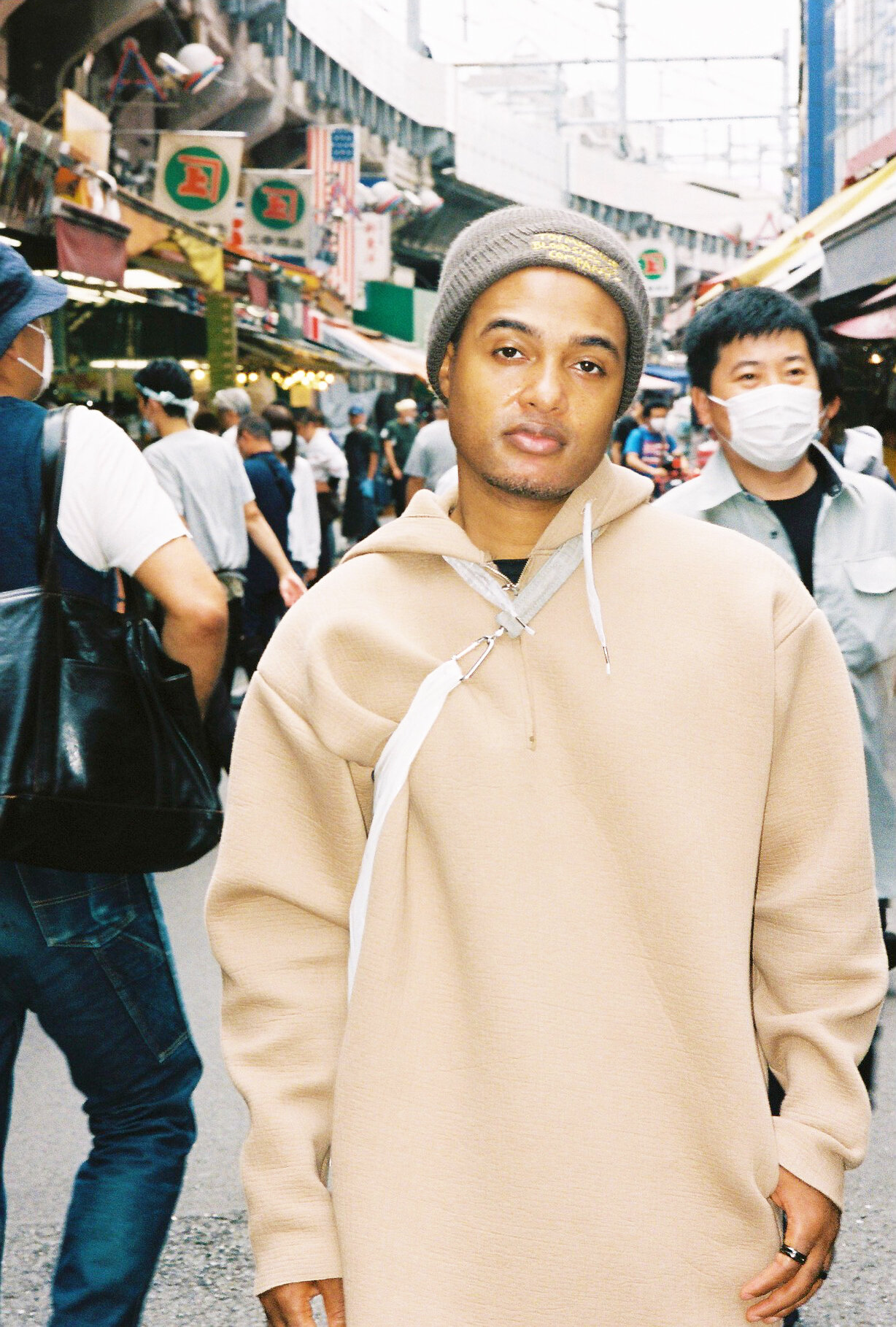

The Casual Connection, Reggie Casual

Photographed by Masahiro Yoshimoto

After three months of planning a shoot over email, Reggie Casual, arrives in Asakusa to meet photographer, Masahiro Yoshimoto, and Tokyo-based stylist, Manami Miyamoto. Even though, Yoshimoto, lives in Osaka, he scouts Asakusa—a district in Taitō, Tokyo, Japan, famous for its vibe of old Tokyo and the Sensō-ji, Tokyo’s oldest Buddhist temple dedicated to the bodhisattva Kannon—far away from home. It takes two hours and twenty-three minutes to travel by bullet train between the city of Osaka to Tokyo, and, Yoshimoto, shows up on the dot because, “Enjoying everything is most important,” he writes to me over translated emails from Kanji to English—sprinkled with hearts and fire emojis.

It’s this particular dedication and good timing that brings us together at the exact locus of where Tokyo’s fashion and street worlds are today. Even better with ‘your boy’ Reggie, who also happens to be a trained dancer, music producer, fashion designer, and founder and host (at least for now) of The Casual—a fashion brand history YouTube channel that introduces Japanese street culture to western fans—with over 16 million views.

“I’d like to think of The Casual as the segue between designer and street,” he says. “Putting these two things together, noticing that there is a way for us to co-exist. We’re still trying our hand at it—in the general sense of the fashion industry. I want to be that middle ground.” It helps that Reggie’s living out his means to create in Japan. To hear him tell it, “The idea is to maintain a semblance of community and consistency,” he says. “That’s the one thing that prevails in Japanese business.”

It’s a little before sunset on a balmy summer evening for me in northern California. Over our video call during Reggie’s local time—10 A.M., GMT—I nod to his experience, reimagining a full-time creative life for myself in Tokyo. It’s hard not to indulge a teeny tiny bite of bliss during quarantine post binging Japanese drama series Tokyo Girl (also known as Tôkyô Joshi Zukan) on Amazon Prime. Except, this isn’t an 11 episode show. This is real life.

Within minutes, I get a sense that Reggie lives in a consistency-is-better-universe. It’s also homogenous—in which he evaluates openly through video essays like “Race Relations in Japan: A Street Fashion and Culture Perspective” on The Casual. “It was really easy for me to get acclimated with Japanese culture and lifestyle,” he says “but one of the things that I definitely had to do was embrace the fact that I was a foreigner in Japan.” In entering this reality, “One of the few things, if I can give anybody some advice coming to Japan, whether they understand the language or not—I speak and read the language—you’re still a foreigner. As long as you’re a foreigner who is a clear foreigner, you’re still going to be treated like that.”

Reggie is a Black man (of mixed heritage), originally from Los Angeles, who grew up in different cities around the US including: Georgia, Illinois, and North Carolina. He also spent some of his early childhood years in Japan, expanding his perception of identity and culture around the world. “My father was in the navy so I traveled around quite a bit as a child,” he says going into detail on why Japan has been his speed from day one. “I just became enamored with the culture as far as how Japanese approach [anything] whether it was design or just life in general.”

What were some of the differences noticed, addressing the obvious—being a Black man in Japan? “To [Japanese] the idea of seeing somebody as their color is almost oblivious to them because they all are the same,” he says. “That kind of dynamic changed my perspective on what being an American is. It’s more of a culture and what we exude. If I were to bring a White person from America and a Black person from America—and I set them in Japan—they have more in common with each other than any Japanese person. They have more in common with each other than any Nigerian they might see. And so that’s what I’m trying to convey through fashion actually; this idea that there is a difference between Japanese and western style. There is a cultural difference. And in order for us to accept culture, we have to be beyond our personal feelings towards any one given ethnicity or society—not to say that’s not important, but it’s to be beyond that. I think one day we’ll get there but right now we’re still learning.”

Through these plops of evenhanded positivity—in the middle of a pandemic—I’m delighted to know that Reggie is getting to play the game on his own terms. “The life that I’ve come into in Tokyo is hard to give up,” he says with a smile. “We don’t care about making so much money. What we care about is getting our idea across and creating a small community because in Japanese fashion—diversity doesn’t come from [Japanese] as individuals [it] comes from the choices we make in our lives.”

You can’t see it on camera, but I start to think to myself this question. Could Japan gain a reputation as a place for Black people; to push beyond the climate of what we know in the west? Picking up on the thread of making a life in Tokyo—Reggie further depicts the significance of acceptance and opportunity. In Japan, “There’s a few levels,” he says. “The reason why Japanese are the way that they are is because this phrase in Japanese. Watashitachi wa nihonjin means we are Japanese. So at the end of the day that prevails over everything. Whatever is good for the community is good for the community at whole; I’m willing to sacrifice that thing. Watashitachi wa nihonjin also has a negative connotation saying that we are Japanese and you aren’t, but the simple fact is that because they have this overarching kind of mantra—what one individual thinks does not prevail over the entire culture. And so what I try to convey to my western compatriots over there; my friends and family over there in America. One of the things that I hope that Americans realize is beyond culture, color, creed, religion—that they get to this sense of we are American.” And so in Japan, “You have to either leave,” he says, “or, you accept it and take advantage. And so that’s what I did. I took advantage of the fact that I knew English and Japanese [being] a clear foreigner, in Japan, as a way to introduce Japanese culture via fashion.”

When Reggie was growing up, he had this idea that there were just too many cool things in life, “and I wanted to do all of them,” he says. Why commit to fashion? “In my years I wanted to do entertainment—singing and songwriting,” he says. “What I found out more about myself is that I was really involved in the creative arts. For me, fashion just became one of those things that I could control as I got older. Those other things like music, dance, and everything—if you’re going to make careers off of them, it takes a lot out of you as you get older. So, it’s not that I gave up on those, it’s just that I realize that fashion [is something] I could do for the rest of my life. And I wouldn’t get weary. My voice wouldn’t leave me. My body won’t get creaky and old. I made a decision based on the future and just calculated decisions based on that.”

For his part, Reggie is dreaming up ways to build The Casual’s community network by inviting guests to talk about what’s happening in fashion—its buildout of The Casual’s YouTube highlights that feature videos anywhere from under-appreciated collaborations to must know manufacturing tips for designers. “To bring fashion under this umbrella is why I came up with the idea,” he says. Even having a clear understanding of international markets and workmanship—Reggie was not always acquainted with Japanese fashion. “Looking back it’s almost embarrassing. I didn’t even know what BAPE was when I first came to Japan because I was more into music and dance at that time,” he says. “As I got into fashion, I wanted to know more. I’m just that kind of person.

When I decide I want to do something I want to know every single thing that I can about it, and so it took me [almost] a year to know who the designers were. And once the rabbit hole was dug I got into Rei Kawakubo, Junya Watanabe, and Jun Takahashi. Beyond the Shinsuke Takizawa’s—who’s with Neighborhood—and of course Nigo—with BAPE—I just started learning more as I got more into it.”

By now, this of course helps coalesce old and new generations of fashion communities in Japan. “The older generation is still quite influential,” he says. “You can’t walk in Japan without knowing Comme Des Garcon and what, Rei Kawakubo’s, done for the entirety of fashion in Japan. When you think about, Rei Kawakubo, she’s the one who kind of spearheaded this entire generation of anti-fashion. She’s the one who gave confidence to a lot of young Japanese designers namely, Chitose Abe [who is] creative director of Sacai and [designers like] Junya Watanabe. And so this entire ecosystem of fashion in Japan is one that you have to respect these older designers. You have newer designers out there. Yoshio Kubo [is] one of my favorite designers right now. He’s doing fantastic things. You have people like Verdy—who’s with Girls Don’t Cry—these are all part of an ecosystem that I have been trying to infiltrate myself for quite a long time, and I’m just lucky to be a whisper in their ear.”

This is why we’re here today. My fiancé introduced me to the growing network and I—at long last—felt connected to The Casual being a place to engage with fashion history and the in-betweens of culture. Something I find to be important in what feels like an industry obsessed with the fantasia of borrowed aesthetics. I have to admit that I don’t have the answers. I’m still reflecting on how I look at things for what they are and are not. That said, it’s still really refreshing to watch mini fashion segments that has range and encourages us to depart from the emphasis on hype. A very important something he learned in fashion for a long time, “And what I think is missing,” he says thinking back to the way fashion was in the late 90’s early 00’s. “I’m anxious to see that again,” he says. “There’s so much more to indulge in. There’s so much access to everything. This is why I cover Japanese fashion. I don’t hate on any brand that’s doing well. Do your thing. Like the brands. But there’s so much than those brands and there’s so much more for you to partake in. It’s a lot easier when you don’t have to worry about how you think other people are going to perceive you and receive you. I miss that. I miss having fun.”

It’s impossible to trace a straight line on what it takes to shape an unparalleled legacy, but Reggie is the type who is up for landing at the goal line. He endorses what works (for the most part) in ways to push culture and personal style forward. “I miss the idea of personal creation,” he says. “I feel like it’s coming back in a different form and that’s encouraging. I’m all for evolution, but let’s take it in terms of fashion. In the 2010’s, what we saw was an exponential growth of follow-ship beyond social media. It kind of manifested itself in real time as well. The idea that we were following others. We were following trends. We were following [what] famous people were wearing. And this is a result of people becoming more affluent. When you make more money, you lose that creative aspect because now you’re looking for other people to give you a sense of style. I’m not saying that I want people to be poor again—even though there’s a big gap between who’s wealthy and who’s not. What I would love is for people to take with that different form that I see manifesting now. This going back to the bespoke kind of styles.

He continues to encourage DIY and research. “You see that on a smaller scale with more of those who are art directed individuals,” he says. “Sometimes they’re not so good at business, but they have such a fantastic view on product [that] it blows all the business out of the water. So that’s encouraging to see. But we’re still in that mode of where can I get that? Tell me where that is? And I’m just the guy who’s like, ‘search for it.’ Go out there, see something, and be inspired by it.” Tearing up the rulebook, “I would never want anybody to be head-to-toe in my label,” he says. “I would like to produce something that you could wear head-to-toe—because it’s not logo-fied. My goal is not to have you wear everything that I make. My goal is for you to be drawn by what I make and come to your own conclusions. Use it to apply to your own sense of style.”

Not too far from where Reggie finds himself—if he were to ever start a fashion collection—most of the times shopping, “it becomes a reference point for my future designs,” he says. “That’s why I started buying clothes in the first place. [A] longer shirt for a person my height is going to look kind of crazy, but if I layer it, maybe I can do this, that, and the third. I’m trying to solve problems and my closet right now is—I’m not going to say is perfect, but it has all the pieces that I would love to take reference from, and that I probably will.”

With one eye on his family and the other on his growing empire, “There was a point in my life where I was just the most confident individual in the world,” he says. “I knew all of things were going to happen to me but until they started happening I was like, ‘Holy crap I didn’t really think they were going to start happening.” Always inspiring, “I believe you need individuals who are like me, who have come into the folds, who understand,” he says. “I’m a little bit more open minded because I look at the problems and say hey that’s a problem and let’s fix that problem rather than just staying in my corner and being stubborn. I’m incredibly flexible with my ideas and people’s opinion.” It’s an admirable quality rare to come across nowadays. Long may he reign.

Originally published in IN #9, FW 2020/21